How Do You Know Wehn a Bally Slot Machine Was Made

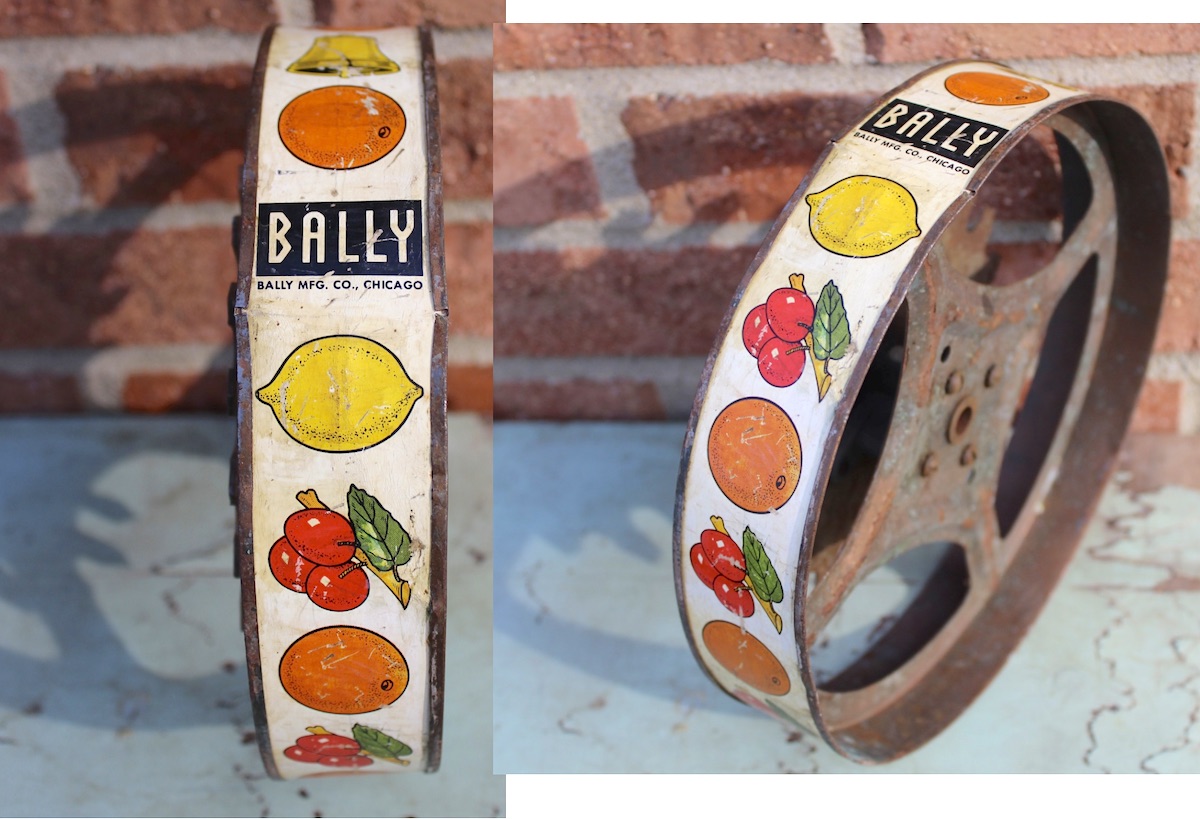

Museum Artifact: Bally Mechanical Slot Machine Reel, c. 1930s

Made Past: Bally MFG Co., 2640 Westward. Belmont Ave., Chicago, IL [Avondale]

Bally is i of the most recognizable and however seemingly untethered brand names in America. It's been associated—depending on your historic period and demographic—with arcade video games, casinos, rollercoaster theme parks, fitness club chains, and, starting in 2021, a stable of regional TV sports networks. The consistent thread, I suppose, is "amusements," and that can certainly be traced all the way to Bally's oft-forgotten Chicago roots as a maker of coin-operated games in the midst of the Great Low.

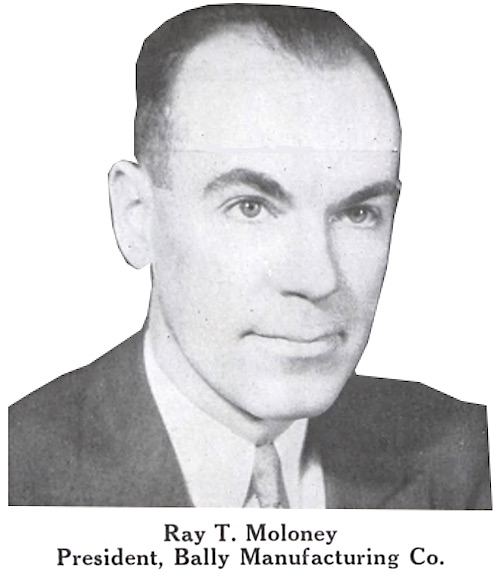

The artifact in our museum collection probable dates back to the 1930s, besides, and would have been used in ane of Bally'south early on slot machines (aka "bell consoles," "iii-reelers," or "fruit machines"), such as the lovely Bally Bell pictured above. Even back then, there was no shortage of controversy when it came to the building, distribution, and management of gambling devices, and without question, Chicago'due south ever-lurking criminal underworld was always an arm'south attain away from whatever so-called "one armed bandit." Withal, Bally's founder Ray T. Moloney seemed genuinely intent on bringing the joys of mod gaming out of the shadows and into the mainstream, setting the tone for how nosotros still think nigh testing our luck and distracting our minds in the 21st century.

[The slot machine fruit reel from our collection would take been installed in one of Bally's early mechanical slot machines. The fruit symbols on the reel dated back to earlier merchandise stimulators which dispensed chewing gum (cash payouts being illegal). If a player matched three fruits when the reels stopped spinning, they'd win that flavor of gum. The fruit icons stayed even as slot machine prizes evolved.]

History of the Bally MFG Co., Part I: A Panthera leo Awakens

"Meeting Ray Moloney for the first time, you feel the spirit of adolescent friendliness that he radiates. Then earlier long, as you swap ideas with him, you notice that hither is a built-in organizer of productive effort . . . a man who knows how to utilise his fourth dimension to get things done." —Automatic Age magazine, September 1932

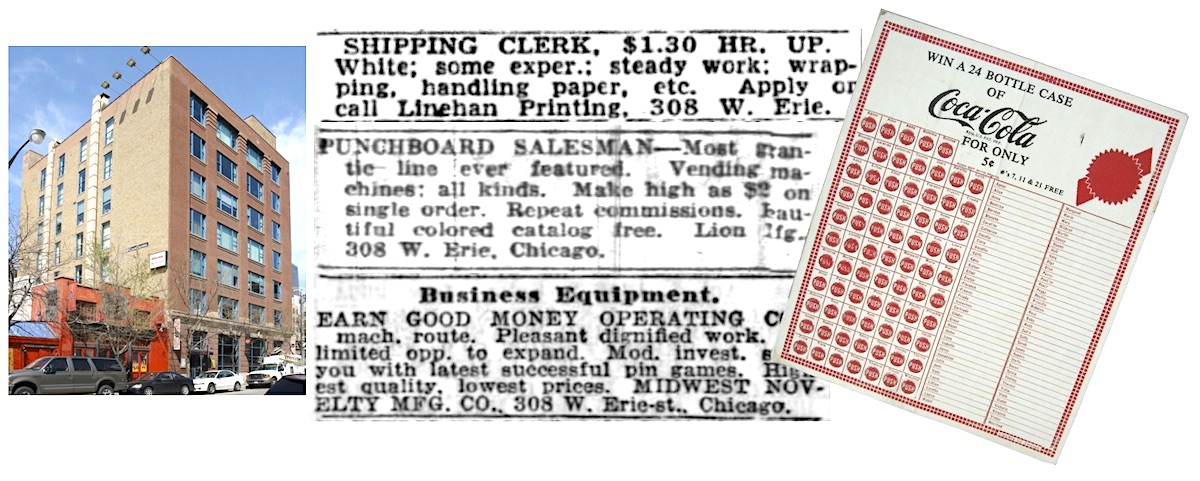

A applied jokester with an affable Irish charm, Ray made friends with ease, and it helped him plot his course. After just a couple years working for the Joseph P. Linehan Printing Visitor, his bosses liked the cut of his jib enough to put him in charge of two new subsidiary businesses. The commencement—launched in 1922—was the Panthera leo Manufacturing Company, which focused on producing "punch boards," the low-budget trade-stimulators that were basically the unregulated scratch-off lottery tickets of their era. Iii years later on, the Midwest Novelty Visitor was established to distribute all of the prizes or "premiums" associated with the punch board concern—usually niggling things similar pocket knives and wallets. By the finish of the decade, Midwest Novelty had too get a distributor for some bigger-ticket items, including gaming machines—thus introducing Ray Moloney to the wider world of coin-operated entertainment.

At the beginning of the 1930s, both King of beasts and Midwest Novelty were still occupying relatively pocket-sized offices in the Lineham printing plant at 308 Westward. Erie Street, merely Moloney saw keen opportunity on the horizon, despite what the deepening economical low might accept suggested. With Americans out of work and not even legally permitted to drink away their troubles, a new gaming manufacture was rapidly filling the void, offering welcome distractions in all shapes and sizes.

[Left: 308 W. Erie Street, former home of Bally, Lion MFG, Midwest Novelty, and Linehan Printing. Center: Classified ads for three of those entities. Correct: A punchboard produced by Lion]

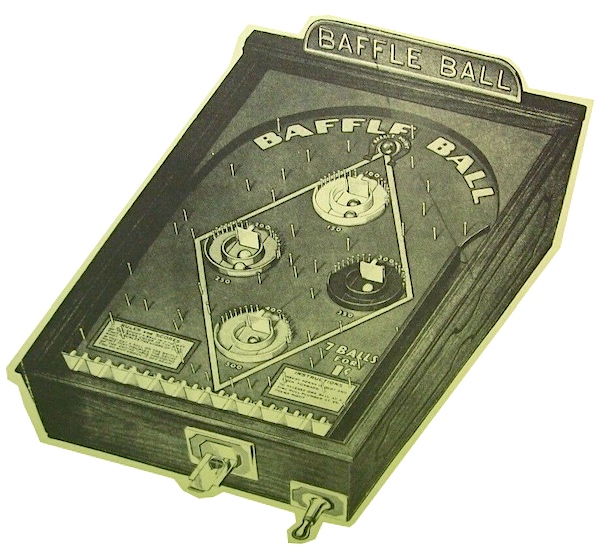

Ray was particularly intrigued by an extremely pop new bagatelle-style tabletop game called "Baffle Ball," which Midwest Novelty started distributing in 1931. Created and manufactured by Chicago'due south D. Gottlieb & Visitor, Baffle Ball was played on a flat board with sporadically placed pins and round cups of varying betoken values. The player would burn a marble onto the board, via a plunger, and promise to get it to country successfully in one of the cups. At the time, the word "pinball" wasn't even a part of mutual parlance however, and this game used no electricity, let alone flippers, bumpers, and bells. Withal, the public was already enamored with the concept and more willing to pay a penny for seven shots at a big score. Those coins, in turn, added upwardly fast, appeasing whatsoever shop owner who installed the game in his establishment.

Ray's son Don Moloney—who was born simply months after the events described—would later say that his father came upward with the idea for his own flat pinball game and promptly built it himself. The more than probable narrative seems to be that Ray got the idea to undercut Baffle Ball, and went out in search of feasible designs for doing and so, eventually paying royalties to a couple fellas named Oliver Van Tuyl and Oscar Bloom to industry their similar pivot game. If not e'er an idea-man himself, Moloney was a very enthusiastic recipient and assessor of other people's ideas, which might be no less valuable a trait.

Ray'southward zeal was also advantageously contagious, enabling him to convince his Lion business organisation partners—Joe Linehan and Charlie Weldt—to fund his new projection with a massive cash investment. The press men had no feel in coin-op game manufacturing, simply they agreed to give it a go, seeing the effort more as a short-term risk on a fad, rather than an heady new borderland for their business.

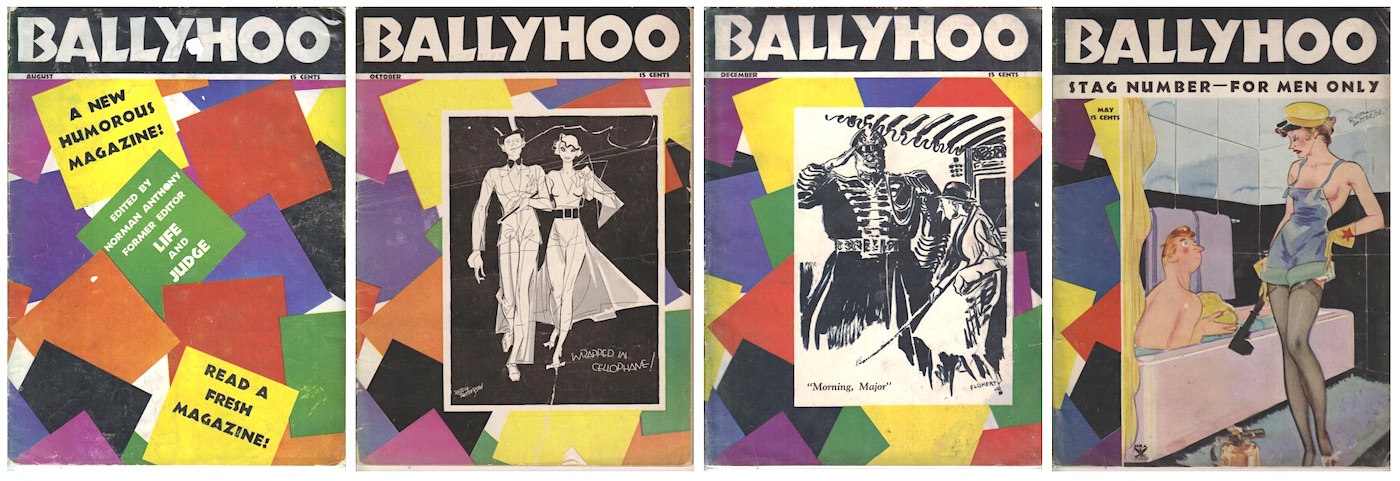

The but affair missing from Van Tuyl and Flower's game design, Moloney had adamant, was some sexual practice appeal—the type of heart-catching colorful artwork that had been vital to Lion's punch board sales. Every bit the story goes, Ray solved this dilemma when he randomly walked past a newsstand and caught sight of an consequence of the popular new men's humor magazine, Ballyhoo. Once again, he was inspired to "borrow" an existing idea, swiping not just the magazine's name for his first pinball game, only the distinctive proto-Playboy fashion of its embrace art, as well [it seems likely that some sort of fiscal agreement was ultimately reached with the magazine's publishers].

And and so Ballyhoo, the game, made its debut in January of 1932, and some other new subsidiary business, shortsightedly chosen the Bally Manufacturing Company, was established to produce information technology. Again, wasting no time and displaying no shame, Moloney booked a Bally + Ballyhoo coming-out political party at the 1932 Coin Auto Expo in Chicago, and soon had the ten,000 attendees singing along with him to his new promotional jingle:

" What will they do in '32?

Play Ballyhoo!

Rainbow colors catch the eye,

Profits climb correct to the sky!

Bally-Hoo'south the game for yous!"

Briefcase sized at 31" x 16" and relatively affordable to operators at about $16.50 per machine ($315 subsequently inflation), Ballyhoo besides quickly roped in the general public with its looks, ease of play, and cheap investment: 7 balls for a penny. Orders quickly outpaced Baffle Brawl, and the effervescent Ray Moloney had a hit on his hands. His far greater accomplishment, though, was somehow beingness fully prepared for what that actually meant.

2. Bally Go Boom

"Right now, hundreds of thousands of men, women, boys and girls are playing BALLYHOO—and the popularity of this sensational new machine is only merely showtime. Clack became a bully success almost overnight. Information technology is destined to be the virtually amazingly popular game ever introduced. That's why we say: What'll they practice through '32? Play BALLYHOO!" —Bally advertising, 1932

"My father had beautiful handwriting," Don Moloney subsequently said. "Anybody learned the Palmer method back and then—and so he just wrote the name. That's been the logo always since."

Fifty-fifty grizzled coin-op veterans couldn't assistance but be impressed by Bally's swaggering debut, and the trade magazines routinely lavished praise on the upstart arrangement.

"Inside a few month's fourth dimension," Automatic Age noted, "and during the nearly acute period of business organisation distress the world has yet known, a new leader has forged boldly to the front in the field of money-operated amusement devices. That leader's growth has been rapid. Its success has been ane of the sensations of 1932. However there is nothing mysterious or baffling about this record of accomplishment."

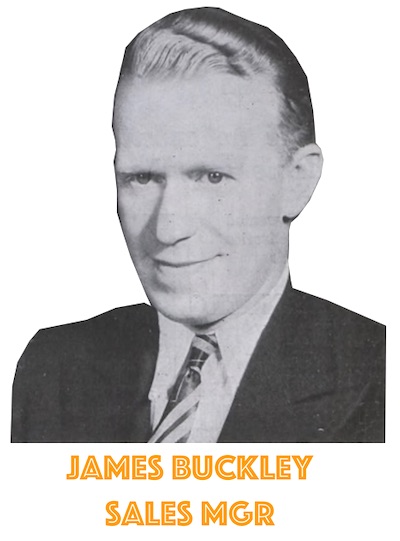

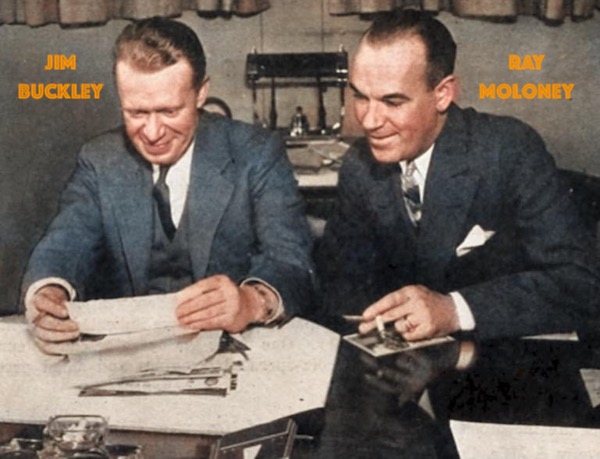

In one case Ray Moloney made the decision to go all-in on Clack, he recruited a new team of similarly minded go-getters to exist his cohorts in the venture, including fellow Irishmen James M. Buckley (sales managing director) and Patrick Millette (production manager), also as advertising managers Alfred Due east. Fox and Herb Jones. While well-nigh of these men were no older than Moloney, they had well established connections and reputations in the coin-op universe, and a keen understanding of how to become a game built, sold, and distributed.

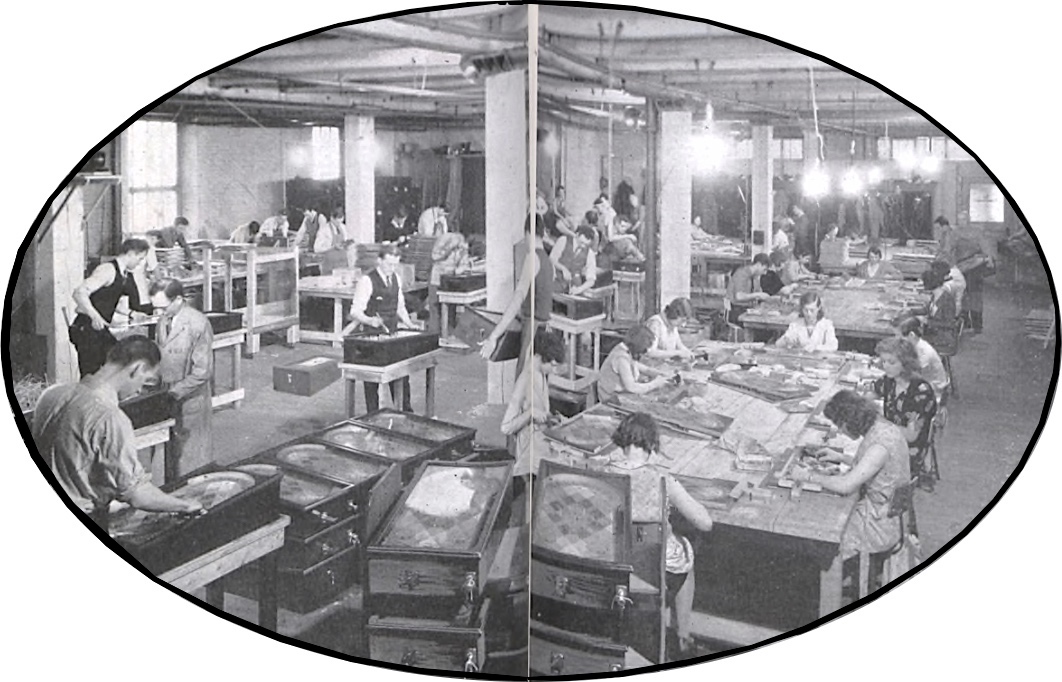

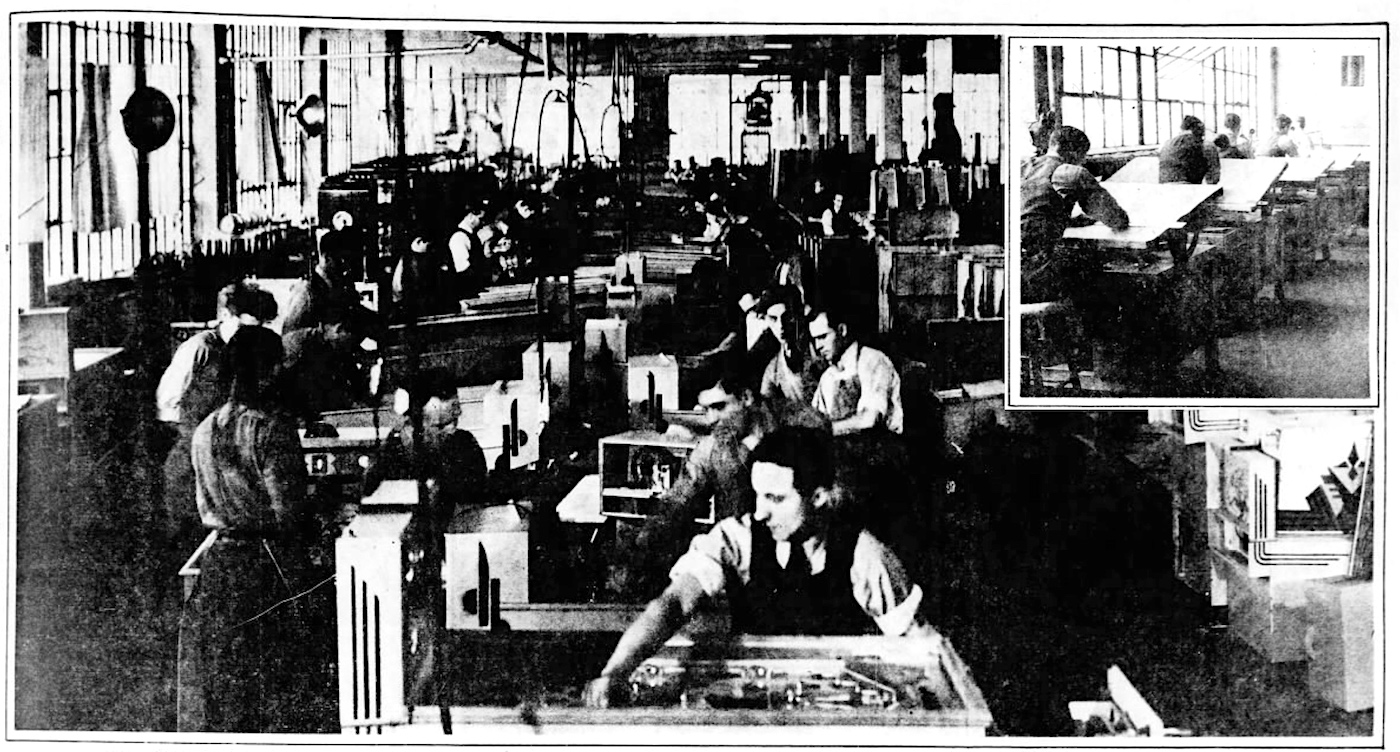

"While mass product methods are utilized to their fullest wherever these are all-time," Automated Age reported at time, "there are several processes painstakingly performed by hand. Every one of the brass nails in the playing board of a Bally board is driven into its exact identify by hand. No magnet hammers are used, for the reason that the location of the nails and their straightness on the board influence the playing of the game."

[Workers assembling Ballyhoo at the Lion/Bally plant at 308 W. Erie Street, 1932]

With the games built up to the needed quality and quantity, information technology was time for sales guru James Buckley (1897-1947) to shine.

The final member of the and so-called "Four Horsemen" of Bally was the ad managing director—starting with Alfred Fox, but quickly followed in the spring of 1932 past Herbert B. Jones, a former paper man who took to coin-op copywriting similar a duck to water. With the powers of the Linehan printing presses at his disposal, Jones was able to curate a quick mythology around each new Bally production, exemplified by his clarification of the Clack follow-up game, Goofy, as a "blaze of color; an orgy of thrills."

Famed humorist Will Rogers came to a similar determination afterward attending one of the large Chicago coin machine merchandise shows. "Information technology's replaced golf, bridge, Kelly pool and the New York Stock Exchange for exercise and gambling," he said. "We will win the next war in a walk if they permit united states of america shoot marbles at 'em."

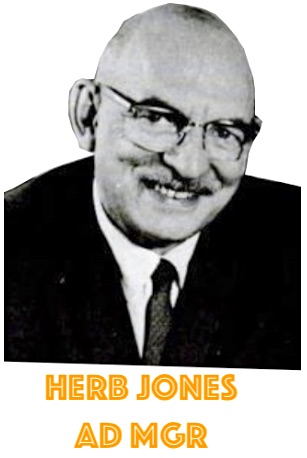

Indeed, any ideas of pinball and other slot machine games being role of a short lived "fad" were extinguished in Ballyhoo'due south wake, as Ray Moloney wisely stepped on the gas pedal rather than coasting on his first large win. Along with buying out Linehan and Weldt'south shares in the Panthera leo MFG Co., he made an ambitious push button to build upwardly a fleet of new Bally games—some designed in-house, others purchased every bit part of the company's admissible policy.

"Some of our most successful games have been adult from the crudest kind of models," Moloney said in 1933, having already rolled out a serial of new best-sellers, including Goofy, Screwy, 3-Band Circus, Bosco, Crusader, Blue Ribbon, Airway, and Rocket. "Judging from the letters nosotros receive, many people are about bashful almost submitting ideas. They seem to feel that they are asking us a favor to have us consider their ideas. Every thought naturally needs development and thorough testing, but you can never tell when a crudely drawn sketch will have the germ of a knockout game. For this reason, every idea submitted to us is studied, not only past myself but past at least 3 other members of the organisation. If any of united states sees merit in the idea, it is turned over to the development department. And, if we later put the car on the market, the man who sent in the thought gets a royalty on every automobile sold."

Moloney best-selling that Bally lost a hefty sum paying out royalties, simply the investment certainly seemed to be well worth it, equally the company became associated with many of the most important gaming innovations of the era, including the first ball-trap characteristic (Airway), the outset progressive scoring format (Monarch), the start automated payout pin-game (Rocket), the offset over-sized table (Colossal), and the outset spring bumper pattern (Bumper).

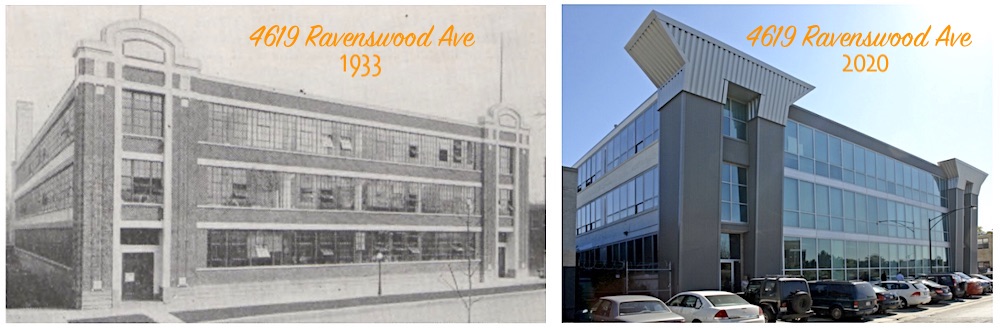

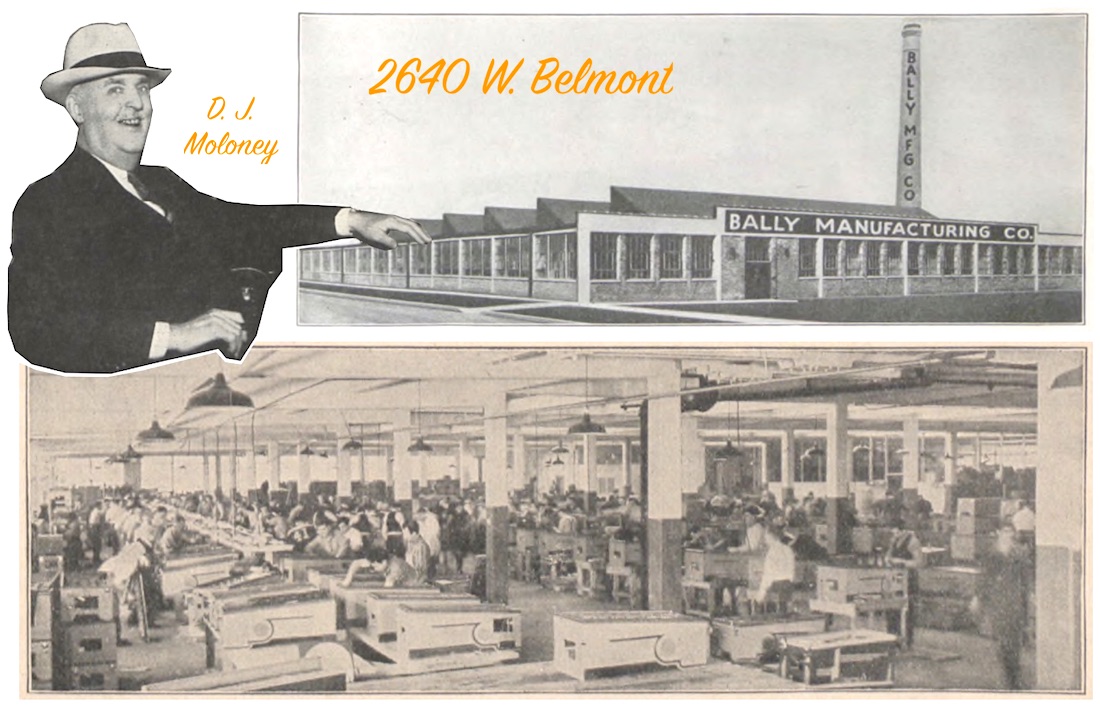

With dozens of games in development by the stop of Bally'south first yr of existence, the Erie Street institute was already pushed across capacity. Then, past Dec of 1933, an additional three-story, 50,000 sq. ft. factory was put into functioning at 4619 Due north. Ravenswood Avenue. Remarkably, this didn't solve the problem either, and past 1935, the third and largest of the Bally plants opened at 2640 W. Belmont Avenue, giving the organization over 125,000 total square feet of space beyond three Chicago facilities—not to mention a growing network of regional warehouses around the country.

"Today we are once again forced to expand in guild to satisfy the overwhelming demand for our new line of machines," Ray Moloney said ahead of the Belmont Artery plant'southward opening.

Notably, Ray recruited his own begetter, Daniel "D. J." Moloney—the former Cleveland steel worker—to come out of retirement and organize the "small regular army" required to move machines and materials into the new building. "It's all in a day's work," D. J. said after the successful migration. "If at that place are any medals to be passed out, manus them to the boys who stood past on this job."

[A look exterior and inside Bally's Belmont Avenue plant in 1935. The building would remain in utilise by the company until the early 1980s. It has since been demolished.]

Iii. "Unethical Operators"

In 1937, still simply five years into Bally's existence, Ray Moloney was toasted by 500 leading money-op industry representatives at a surprise Chicago banquet in his honor. In that location, Lee South. Jones of the American Sales Corporation proclaimed that "No one man has done every bit much to promote prosperity in the coin machine industry or and so richly deserves the gratitude of anybody in the manufacture every bit Ray Moloney."

"Bally's busy!" he told a reporter, challenge to be in the midst of the company'due south best twelvemonth yet. "We continue the manufacturing plant going past offering a hit game for every type of amusement functioning, from counter to console class, and everything in between."

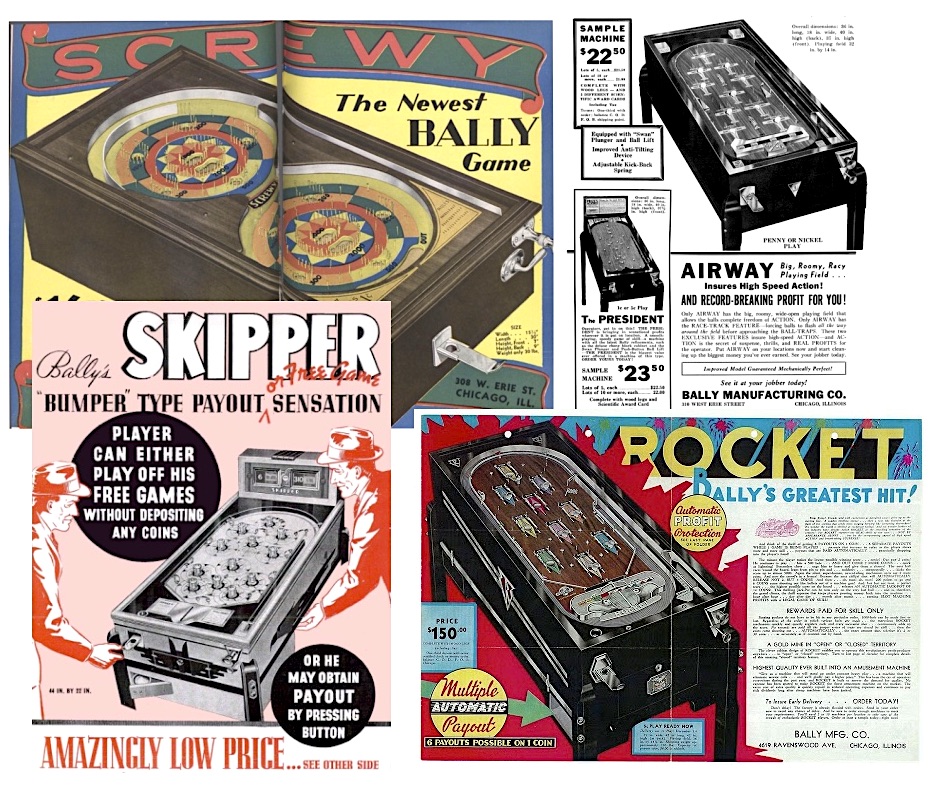

Moloney had a squad of eleven engineers on staff, tasked with completing another exciting, marketable game design most every other calendar month in order to keep up with the other xx-odd coin-op manufacturers in Chicago solitary. The "everything in between" strategy also included an awful lot of games that relied more on hazard than skill, including—arguably—the pinball machines themselves, which yet didn't have controllable flippers, and thus didn't necessarily favor a steadier manus.

[Principal image: Bally pinball associates line, 1937. Upper correct corner: Applied science department]

While game operators, politicians, and constabulary increasingly debated the claim and legality of pinball, some of Bally's more popular new offerings landed far more blatantly into the "gambling game" category, especially its new reel-based bong consoles—what we'd now generally refer to as slot machines.

Early Bally slots, like the "Bally Bell" and its upright cousin the "Bally Reserve Bell," utilized the familiar spinning fruit reels similar the type in our museum collection. Operating these machines with bodily cash payouts was illegal in most places outside of Las Vegas, notwithstanding—and even slot machines that dispensed gum, cigarettes, or other prizes to winners were still widely frowned upon for their well-known connections to illegal gambling rings and the underworld.

There were some more family-friendly games put on the market, too, such as 1938'due south "Bally Baskets," which Ray Moloney described every bit a "one-hundred per centum, simon-pure legal game with no ifs or buts nearly it. In fact," he added, sounding more than a fiddling bit defensive, "it is absolutely incommunicable to devise any kind of award system to apply to the game. That ways that the operator who opens upwardly his territory with Bally Baskets will be able to proceed it open up, as no unethical operator tin come along and spoil the state of affairs by offer prizes."

It was easy to arraign "bad operators" for exploiting Bally products, but in Chicago, at that place was only so much intermission of disbelief one could manage when it came to separating a gambling machine manufacturer from the mobsters who ran the gambling rings.

"I know the Mafia tried [to become involved]," Ray's son Don Moloney later recalled, "but my father was very cautious."

Cautious or not, the Bally MFG Visitor was implicated in 1941—along with Mills and several other Chicago manufacturers—for selling carloads of slots machines directly to i of the metropolis's most notorious gambling syndicates, led past longtime Al Capone crony Jack "Greasy Pollex" Guzik. America's entrance into World War II largely helped bury that story simply a few days afterwards, but Ray Moloney still took the step of employing a onetime Clandestine Service agent, Tom Callaghan, as a personal adjutant in the years that followed.

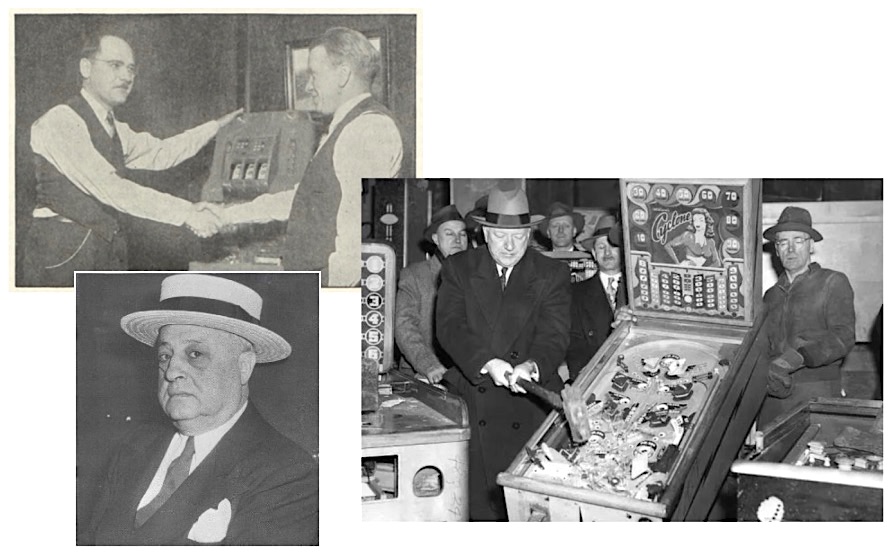

[Top Left: Bert Perkins, assistant sales manager, greets Jim Buckley next to a Bally Bell slot machine, 1939. Bottom Left: Jack Guzik (aka Jake), head of the 'Big four' gambling syndicate and a big buyer of Bally slots. Right: New York Metropolis police commissioner Willam P. O'Brien smashes a pinball motorcar in a raid in Brooklyn]

IV. "Giving the Axis the Ax"

"Excuse me for living has too often appeared every bit the motto of the money machine industry," Bally advertising man Herb Jones wrote in September of 1941, "a motto which, while never expressed in written or spoken works, has been implied past the apologetic manner in which nosotros have discussed our industry with the public. . . . Let's tell our story straight. Our industry exists because the difficult-working, hard-playing American public eagerly buys our product—welcomes the relaxation, the release from worry, the low-cost amusement we create and sell. Let's forget the economical double talk and concentrate on selling what we actually have to sell—America's greatest, most democratic, nationwide, continuous-functioning bear witness!"

Herb Jones, as Bally's master wordsmith, was doing his best to re-frame coin machines as a patriotic function of American life, rather than a growing symbol of post-Prohibition crime and excess. In the end, the manufacturing demands of Earth War 2 helped his propaganda campaign more than any long-winded ad copy could.

Bally had already taken on some regime contracts for the Centrolineal crusade before Pearl Harbor, and by January of 1942—a month subsequently the U.S. officially entered the war—Ray Moloney announced more defense contracting on the way, merely too a house commitment to continue making gaming machines. "Plans are existence rushed to convert boosted Bally production lines to Uncle Sam's big job of giving the Axis the Ax," he said. "Forth with our war work and consistent with our industrial duty, we will, of course, continue to serve the American operators—who, in plough are serving America by providing the convenient, low-cost recreation and so vital to morale."

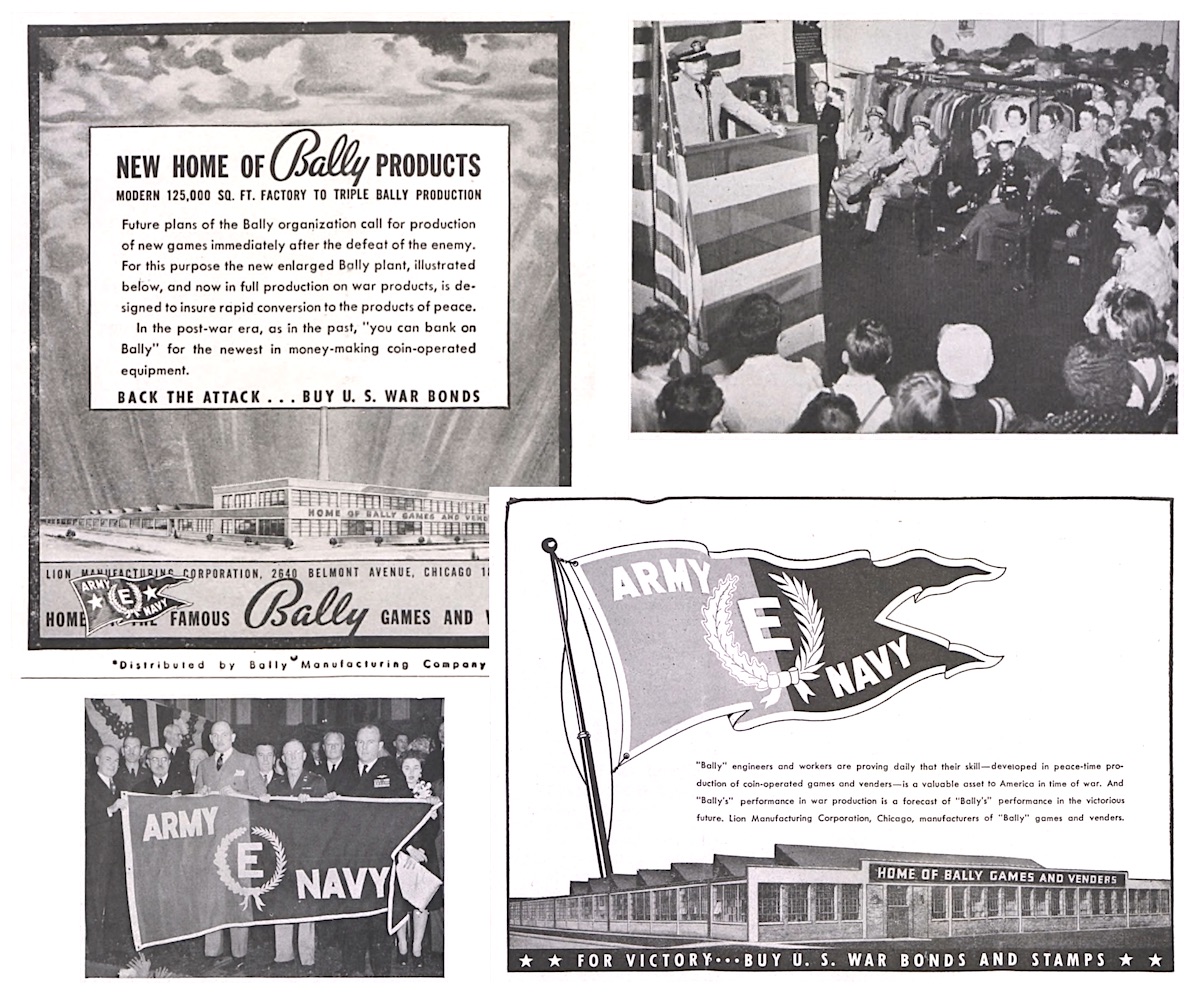

Moloney might have been resistant to shift 100% of his mill forcefulness to defense force contracts at first, but past 1943, that'due south exactly what had happened—and information technology really proved more profitable and beneficial to Bally's reputation than he might have expected, beginning with the government-aided expansion of the Belmont Avenue plant to 125,000 square feet.

[Bally expanded its plant and earned an "E" Flag for its war production, thanks to the efforts of Ray Moloney, his blood brother George Moloney (production), Herb Jones (advertising), Bert Jenkins (sales), Ralph Nicholson (personnel), Roy Guilfoyle (VP and controller), Don Hooker (chief electrical engineer), Herm Selden and Nick Nelson (development engineers), Ed Berkley (superintendent), Jerry Girardin (main inspector), Hugh Harries (supervisor of materials), and W. C. Billheimer (purchasing amanuensis), among many others]

Keeping things in the family unit in one case more, Ray put his younger brother George Moloney in charge of much of the war production try, while on the promotional cease, Herb Jones called on the public to "Buy U.S. War Bonds!"

"[George] Moloney's death is particularly tragic," Billboard reported, "coming at a time when he should have been wearing the laurels of official recognition for his part in the war try. . . . Importantly to him belongs credit for the rapid conversion of the Bally from noncombatant to war product."

5. Succession

Losing his brother was just i of many difficult blows a still young Ray Moloney faced at the meridian of his success, having already lost his begetter three years prior. There were hardships of a business concern sort, too, as a fast return to civilian product later on WWII was hampered by another major military conflict, the Korean War, forth with a new federal law which made it illegal to send slot machines and other gambling-associated games across country lines.

"All the major slot car manufacturers had been in Chicago until that fourth dimension," Ray's son Don Moloney explained in a 1996 interview. "And then all of them except Bally moved to Nevada. But my begetter felt he didn't want to eliminate 500 jobs in Chicago . . . so he started concentrating on arcade games and the kiddie rides."

In the 1950s, Bally gradually re-emerged with a new line-up of cuddlier offerings, from arcade bowling, billiard, and shooter games to the coin-operated kiddie rides that enticed visitors outside of 5-and-dime stores, candy shops, and groceries.

In a 2007 interview, Ray Moloney'southward nephew Earle Moloney Jr. recalled visiting his uncle'due south manufactory as a kid and getting to attempt out the new games before they hit the market place.

"It was like having a swimming pool in your backyard," he said. "To be able to accept all your buddies over to Bally and have them into the exhibit and permit them play all the new games made yous a real pop guy."

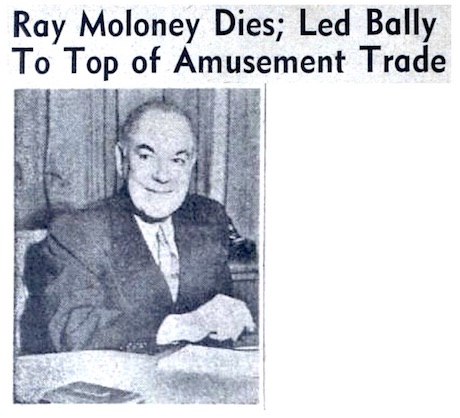

The good times, again, didn't last for long. Ray Moloney died in 1958, shy of his 60th birthday, leaving his wife Edna and sons Ray Jr. and Donald in charge of the family business. The parent visitor of that business concern, incidentally, was still the good old Lion Manufacturing Co. that Ray had formed back in the 1920s; simply now it came with a whole hive of subsidiaries that all contributed to the gaming machine empire, including Bally, a separate Bally Vending Corporation, the Grand Woodworking Company, Como Manufacturing Co., Ravenswood Spiral Machine Corp., Marlin Electric Co., and Comar Electric Co. (headed by Ray'south blood brother Earle).

In theory, Ray Moloney would have taken condolement in his sons, both in their 30s, taking over where he'd left off, but co-ordinate to 1 of those sons, that wasn't necessarily the case.

"He didn't desire us at Bally," Don Moloney said in 1996. "We never understood why. It was very curious. When I was in high school, I would go over to the factory merely out of marvel, and then I could understand the games. But he never wanted us in the business."

Upon the death of Ray Moloney in 1958, Tribune scribe Herb Lyon wrote, "The town will miss i of its sweetest, happiest guys—Ray Moloney, electronics manufacturer, who passed abroad at Columbus Memorial hospital. Ray lavished gifts and dough on obscure people, as he did the town with a never failing grin, bringing cheer to those who needed a lift." Another longtime friend of Ray's, Jack Sloan, wrote in Billboard: "Ray was of a school of dedicated men, defended to the proposition of providing depression-price amusement for the 'man-on-the-street,' the man who could non afford to patronize the race tracks, grand opera, My Fair Lady, etc. Among the now comparatively few hardy and enterprising manufacturers of amusement machines who have survived in this difficult industry, Ray had no peer."

VI. The New Irishmen

The Moloney era at Bally ended on a particularly lamentable note, equally the auction of the business organisation was quickly followed by the decease of Ray Moloney, Jr., at the historic period of just 42. In that location was also some questions nigh the new investment group that acquired the business organisation, led by longtime Bally employee William O'Donnell, and how it had scraped together $1.two 1000000 out of the ether. Whispers of mafia entanglements returned.

O'Donnell dissolved the Panthera leo MFG Co. and re-formed it equally the Bally Manufacturing Corporation in 1969, with shares offered to the public for the first fourth dimension. In the '70s, the upswing continued, as Bally purchased Chicago Midway Manufacturing, which was already pioneering a new era of arcade amusements with video games like Pac Man and Galaga.

Company president James J. Barrett guided the new video game craze much as Ray Moloney had decades earlier with Ballyhoo, and also established a new plant in suburban Bensenville to ramp up pinball manufacturing, now that many cities were finally loosening outdated bans on the machines (thanks in part to The Who's rock opera Tommy establishing the talent-based aspect of the game).

Unfortunately, when CEO Bill O'Donnell made his first move to establish a Bally-sectional casino in New Bailiwick of jersey, he left the rapidly growing company vulnerable to a level of scrutiny that might best accept been avoided.

The New Jersey Casino Control Commission started digging around, and soon followed the breadcrumbs between some of Bill O'Donnell's key investors and organized law-breaking, including New York mobster Gerardo Catena. The Commission responded with an ultimatum: Bally could accept its casino if O'Donnell left the visitor, which he reluctantly did.

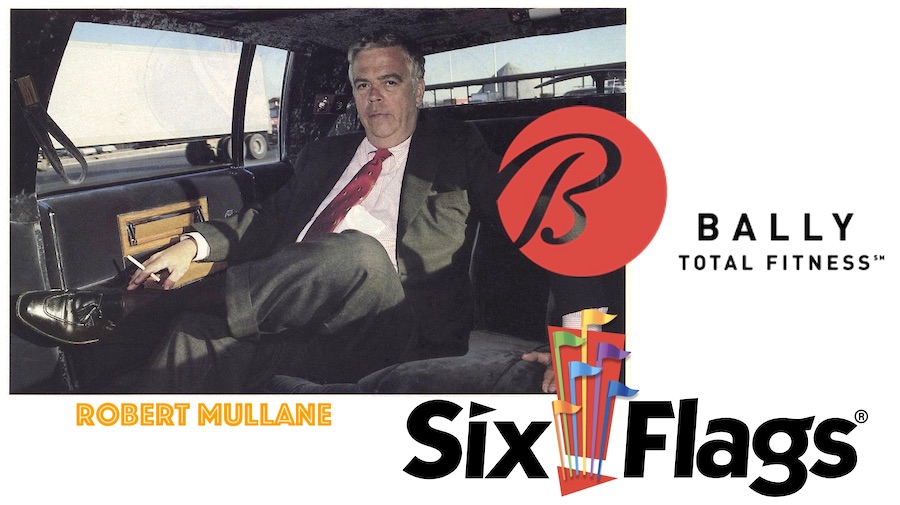

Depending on who you ask, then, Bill O'Donnell either transformed Bally into the diversified corporation it is today, or he recklessly nearly killed it entirely. His successor, notwithstanding some other Irishman named Robert Mullane, fabricated some immediate big moves of his own, acquiring the pop Six Flags chain of theme parks and a fettle club business organization chosen the Health & Tennis Corp. of America, which paved the way for the Bally Full Fitness chain of health clubs (Mullane was notoriously a chainsmoker himself, only correctly saw practiced money in the fitness sector). He also helped become Bally into the country lottery racket; the government-sanctioned formed of gambling that congressmen never seem to crack down on.

On the down side, Mullane did miss the boat on a few disquisitional things, including the video poker phenomenon, despite having the concept laid at his doorstep at its inception. Distracted by theme parks and fitness centers, Bally was straying from its roots to the point that it sometimes let golden opportunities fall straight between its flippers. The visitor as well ceded most of its game manufacturing to its Midway division, and left the Belmont Avenue plant behind afterward fifty years, moving the corporate headquarters to a high-rise near O'Hare Aiport at 8700 Due west. Bryn Mawr Avenue.

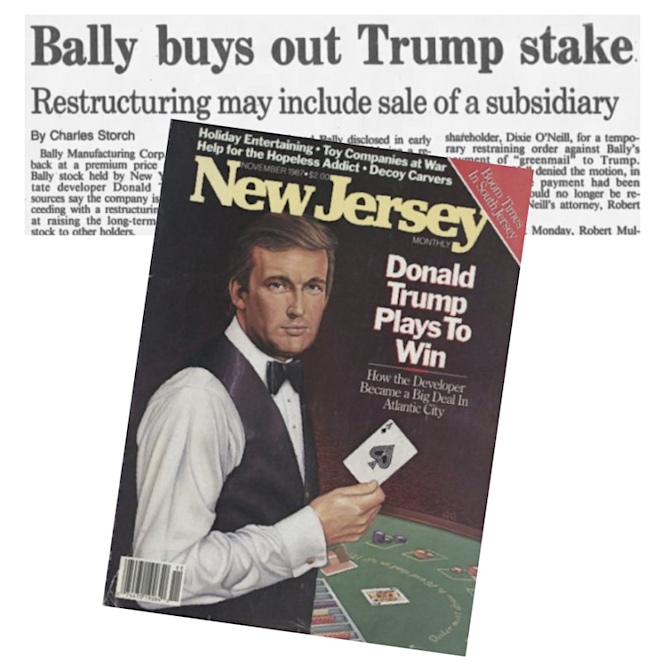

VII. Bally vs. Trump, and the End of an Era

In 1985, with Bally seemingly getting in over its caput in the casino business, one of its stockholders—a argent-spoon real estate developer named Donald Trump—threatened a hostile takeover. Trump already owned two casinos in Atlantic City, and wanted to add together Bally'south Park Place Hotel to his collection. Robert Mullane responded past non merely suing Trump, but outfoxing him. Since New Jersey regulations prohibited anyone from owning more than three casinos, Bally quickly purchased a second 1, the Golden Nugget. The reason? If Trump tried his takeover, he'd now be in possession of 4 casinos in total, rendering the move illegal under state law.

Information technology was too a costly i that soon led to a financial reckoning.

Bally was, by any measure out, the largest gaming company on Earth at this point, but keeping the juggernaut moving in the right direction required lightening the load. "By 1990," co-ordinate to the Tribune, "the visitor was defaulting on loans and struggling to turn profits at its casinos." Sadly, Mullane had also failed to secure a deal with the Illinois state lottery, and responded by re-assessing his remaining Chicagoland facilities in Franklin Park and Bensenville.

In 1988, Bally sold off its amusement games division—the pinball and arcade games that the brand congenital its identity on—to a competitor, WMS Industries; the former Williams Electronics. A year afterward, a new factory was built in Las Vegas, and the exodus of jobs from Chicago began.

"After 58 years, Bally and i,000 jobs are moving out of state," Don Moloney mourned in a alphabetic character to the editor of the Tribune in 1989—although he didn't blame Bally executives for the decision. "It's because of shortsighted, intransigent elected officials," he wrote, "who somehow remain in office despite the damage they do to the state'south economy."

[Photos of the longtime Bally plant at 2640 W. Belmont in the late 1970s, posted by "Mr. Bally" on pinside.com. The company left the establish in the early on '80s, and ended most remaining Chicagoland manufacturing by the early '90s]

Ultimately, another wealthy New Jersey businessman, Arthur Goldberg, succeeded in the same sort of Bally takeover that Trump had tried a few years before; grabbing the reins from Mullane in 1990—to add insult to injury, Mullane was afterward sued for having misappropriated Bally assets and "other abuses."

Not to be outdone, Goldberg somewhen ran into some legal troubles of his ain, defendant of bribing Florida politicians while trying to go gambling legalized in the state. Goldberg would also famously sell all of Bally's casino properties to Hilton Hotels in 1996, effectively severing any connections to the original Chicago era of the Bally MFG Co., and beginning a new age of "Bally Amusement."

Ray Moloney's original Bally script logo has changed hands through a half-dozen different licensing deals over the past 25 years, culminating in a Rhode Island gaming company called Twin River Worldwide Holdings buying the trademark for $20 million in 2020 and rebranding itself as "Bally's Corporation." Having no connexion to Bally history outside of the logo, the new Bally's Corp operates close to a dozen casinos, and its sports betting services will be integrated with the programming of the former Fox Sports regional TV networks in 2021.

Real estate, mass media, national legalized sports betting . . . quite an evolution from a trivial tabletop diversion called Ballyhoo.

Sources:

"The Bally Story: 1931-1966" – Billboard, October 29, 1966

Bally: The Globe's Game Maker, by Christian Marfels

They Create Worlds: The Story of the People and Companies That Shaped the Video Game Industry, Vol. I: 1971-1982, by Alexander Smith

"Ideas with a Punch Put Bally on Top" – Automatic Age, September 1932

"The Process of Converting Ideas Into Games" – Automatic Age, September 1933

"Bally Housed in New Mod Plant" – Coin Auto Periodical, Dec 1933

"Interview of the Calendar month" – Automatic Age, July 1934

"Bally Adds Giant Factory to Present Facilities" – Automatic Age, April 1935

"Bally Boasts Consummate Line" – Automatic Historic period, December 1937

"Bally Baskets in Production" – Automatic Historic period, January 1938

"Big Four Pocket Riches; Capone Believed Cut In" – Chicago Tribune, Oct 28, 1941

"Slot Machine Maker'southward Books Confirm Expose by Tribune" – Chicago Tribune, December 5, 1941

"Ban on Aircraft Slot Machines Hits City Firms" – Chicago Tribune, Jan 3, 1951

"Diversification Keys Lion Mfg. Organization" – Billboard, Jan 7, 1956

"Ray Moloney Dies; Led Bally to Elevation of Amusement Trade" – Billboard, March 3, 1958

"Bally Manufacturing Eager to Make Big Play for Profits" – News-Printing (Fort Myers, FL), January 10, 1988

"Bally to Build Manufacturing Constitute in Nevada" – Reno Gazette-Periodical, May 5, 1989

"The Loss of Bally" – letter of the alphabet by Don Moloney, Chicago Tribune, May 14, 1989

"Bally Manufacturing Corporation History" – International Directory of Visitor Histories, Vol. 3. St. James Press, 1991

"Clack Over Goldberg Inappreciably Whole Bally Saga" – Chicago Tribune, June 17, 1996

"James J. Barrett: Bally Primary, Imported Pac Man" – Chicago Tribune, Jan 17, 2004

"Family Ties Counterbalance on Bally, Ex-CEO" – Chicago Tribune, April 3, 2005

"Pinball Magician Bally Celebrates 75th Ceremony" – Daily Spectrum (Saint George, UT), June xv, 2007

Source: https://www.madeinchicagomuseum.com/single-post/bally-mfg-co/

Postar um comentário for "How Do You Know Wehn a Bally Slot Machine Was Made"